psychiatrist were straight with me that they were not the best people to deal with Military Sexual Trauma which is a event not a disorder and that every VA medical center has a Military Sexual Trauma Coordinator to oversee the screening and treatment referral process so my psychiatrist placed a call to the VA medical center in East Orange NJ who then had her call the VA medical center at Lions NJ and after 20 minutes with no help she said she would call the VA medical center in Bay Pines Fla and let me know at my next visit she started me on meds for PTSD; and other anxiety disorders; Depression and other mood disorders. When I went back to her she gave me the telephone number at Bay Pines and said good luck! as she was still waiting for a answer I called that day and a very nice social worker gave me the number for the MST Coordinator at Lions and East Orange who referred me to the Vet Center in Bloomfield NJ which is about a hour and a half from my home. I started to go to a therapist but do to many factors it was not working for me. The Vet Center opened a new center in Lakewood NJ which is about 15 minutes from my home and I started with a new therapist there in Oct 2010 I have made great progress with this therapist and now also have group therapy for male survivors. Sorry I tend to be long winded what I was trying to say is you have to find who is right for you. Here is some info from the VA website Finding and Choosing a Therapist

Listed below are resources to help you choose and locate a therapist who is right for you. A professional who works well with one person may not be a good choice for another person. A special section for Veterans is included.

Finding a therapist

There are many ways to find a therapist. You can start by asking friends and family if they can recommend anyone. Make sure the therapist has skills in treating trauma survivors.

Another way to locate a therapist is to make some phone calls. When you call, say that you are trying to find a provider who specializes in effective treatment for PTSD, such as cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT).

- Contact your local mental health agency or family doctor.

- Call your state psychological association

- Call the psychology department at a local college

- Call the National Center for Victims of Crime's toll-free information and referral service at begin_of_the_skype_highlighting 1-800-FYI-CALL end_of_the_skype_highlighting. This service uses agencies from across the country that support crime victims.1-800-FYI-CALL

- If you work for a large company, call the human resources office to see if they make referrals.

- If you are a member of a Health Maintenance Organization (HMO), call to find out about mental health services.

Some mental health services are listed in the phone book. In the blue Government pages, look in the "County Government Offices" section. In that section, look for "Health Services (Dept. of)" or "Department of Health Services." Then in that section, look under "Mental Health."

In the yellow pages, therapists are listed under "counseling," "psychologists," "social workers," "psychotherapists," "social and human services," or "mental health."

Information can also be found using the Internet. You may find a list of therapists in your area. Some lists include the therapists' areas of practice. Listed below are some suggested websites:

- Center for Mental Health Services Locator. This services locator is on the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) website. The site also provides a Frequently Asked Questions about mental health.

- Anxiety Disorders Association of America* offers a referral network. begin_of_the_skype_highlighting (240) 485-1001 end_of_the_skype_highlighting.(240) 485-1001

- ABCT Find a Therapist Service*. The Association for Advancement of Behavioral and Cognitive Therapies (ABCT, formerly AABT) maintains a database of therapists.

- Sidran* offers a referral list of therapists, as well as a fact sheet on how to choose a therapist for PTSD and dissociative disorders. begin_of_the_skype_highlighting (410) 825-8888 end_of_the_skype_highlighting. (410) 825-8888

Your health insurance may pay for mental health services. Also, some services are available at low cost according to your ability to pay.

Help for Veterans

VA Medical Centers and Vet Centers provide Veterans with mental health services. These services may cost little or nothing, according to a Veteran's benefits and ability to pay. Following discharge after deployment to a combat zone, you should enroll for VA services. You are then qualified for care for conditions that may be related to your service.

VA PTSD Program Locator: Use this online tool to find a PTSD Treatment program or VA PTSD treatment specialist at a VA facility near you. You can also go online to read more about services at Vet Centers.

Other resources include:

- The VA Health Benefits Service Center toll free at begin_of_the_skype_highlighting 1-877-222-VETS end_of_the_skype_highlighting1-877-222-VETS

- The Vet Centers' national number begin_of_the_skype_highlighting 1-800-905-4675 end_of_the_skype_highlighting1-800-905-4675

- VA Mental Health for Returning Veterans

- VA Returning Service Members (OEF/OIF) Page

- My HealtheVet

VA Medical Centers and Vet Centers are listed in the phone book. In the blue Government pages, look under "United States Government Offices." Then look for "Veterans Affairs, Dept of." In that section, look under "Medical Care" and "Vet Centers - Counseling and Guidance."

Finding a support group

The National Center for PTSD does not provide PTSD support groups. Many local VA Medical Centers have various types of groups. Listed below is information on how to find support groups online or in your area.

- Anxiety Disorders Association of America* offers a self-help group network.

- National Alliance for Mental Illness* (NAMI) has a website with information for those with mental illness. You may also find family support groups in different states.

- About.com's PTSD Forum* An online discussion forum.

Choosing a therapist

There are a many things to consider in choosing a therapist. Some practical issues are location, cost, and what insurance the therapist accepts. Other issues include the therapist's background, training, and the way he or she works with people.

Some people meet with a few therapists before deciding which one to work with. Most, however, try to see someone known in their area. Then they go with that person unless a problem occurs. Either way, here is a list of questions you may want to ask a possible therapist.

- What is your education? Are you licensed? How many years have you been practicing?

- What are your special areas of practice?

- Have you ever worked with people who have been through trauma? Do you have any special training in PTSD treatment?

- What kinds of PTSD treatments do you use? Have they been proven effective for dealing with my kind of problem or issue?

- What are your fees? (Fees are usually based on a 45-minute to 50-minute session.) Do you have any discounted fees? How much therapy would you recommend?

- What types of insurance do you accept? Do you file insurance claims? Do you contract with any managed care organizations? Do you accept Medicare or Medicaid insurance?

Who is available to provide therapy?

There are many types of professionals who can provide therapy for trauma issues. Below we describe some of the most common of these professionals.

Clinical Psychologists

Psychologists are trained in the area of human behavior. Clinical psychologists focus on mental health assessment and treatment. Psychologists use scientifically proven methods to help people change their thoughts, feelings, and behaviors.

Licensed Psychologists have doctoral degrees (PhD, PsyD, EdD). Their graduate training is in clinical, counseling, or school psychology. In addition to their graduate study, licensed psychologists must have another 1 to 2 years of supervised clinical experience. A license is granted after passing an exam given by the American Board of Professional Psychology. Psychologists have the title of "doctor," but they cannot prescribe medicine.

Clinical Social Workers

The purpose of social work is to enhance human well-being. Social workers help meet the basic human needs of all people. They help people manage the forces around them that contribute to problems in living.

Certified social workers have a master's degree or doctoral degree in social work (MSW, DSW, or PhD). To be licensed, clinical social workers must pass an exam given by the Academy of Certified Social Workers (ACSW).

Master's Level Clinicians

Master's Level Clinicians have a master's degree in counseling, psychology, or marriage and family therapy (MA, MFT). They have at least 2 years of training beyond the 4-year college degree. To be licensed, master's level clinicians must meet requirements that vary by state.

Psychiatrists

Psychiatrists have a Doctor of Medicine degree (MD). After they complete 4 years of medical school, they must have 3 to 4 years of residency training. Board certified psychiatrists have also passed written and oral exams given by the American Board of Psychiatry and Neurology. Since they are medical doctors, psychiatrists can prescribe medicine. Some also provide psychotherapy.

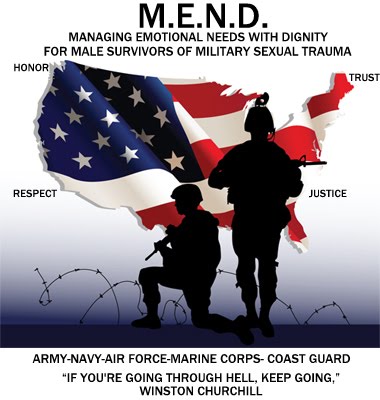

Till next time remember what Winston Churchill said

"IF YOU'RE GOING THROUGH HELL, KEEP GOING"